Pandit Birju Maharaj and the Nature of Rhythm

Last Wednesday, Sepia Mutiny posted a piece about Kathak in San Francisco, and mentioned that

Pt. Birju Maharaj would be in New York on Friday for a performance. For me, this was like hearing Nijinsky was in town to dance one last time, and right across the Park, too.

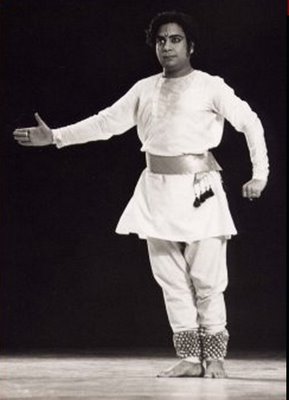

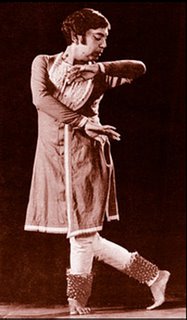

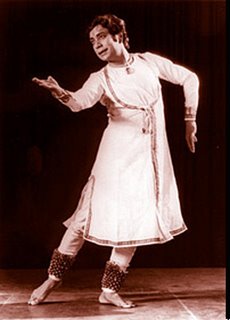

Pt. Birju Maharaj would be in New York on Friday for a performance. For me, this was like hearing Nijinsky was in town to dance one last time, and right across the Park, too.Briju Maharaj is the greatest living exponent of Kathak, as well as being the inheritor of the Lucknow Gharana, which has produced, arguably, the finest form of Kathak, leading other forms through at least two centuries. He has been known as a legend in his time since earliest youth, which led me to believe, as a child, that he was already advanced in years.

This and other other delusions gave Friday's simply irresistible opportunity an urgent tone, which meant that I had to set aside my tickets to the New Yorker Festival.

This and other other delusions gave Friday's simply irresistible opportunity an urgent tone, which meant that I had to set aside my tickets to the New Yorker Festival.

At Symphony Space, the crowd gathered in the lobby in a semi-social manner, with that style of Indian nonchalanace sometimes interpreted as chaos. The guard was provoked to speak out: "All those here for the In'nian Show, step to your left!" she cried. But there was no-one there who wasn't, although everyone shuffled a tad to their left and eventully lined up. Time was on hold as the audience drifted in and the musicians, including Utpal Ghoshal on tabla, Jayanta Banerjee on sitar, Debasish Sarkar and a beautiful young woman who sang wih soft precision, treated the meandering house to a sophisticated warm up.

Normally, I rail against lecture demonstrations, but here the lecture was pithy and the demonstration not to be missed. For his first appearance onstage, Pt. Maharaj wore a a fine golden necklace over his pale cream Akbari jama, tied on the right, embellished with Benarasi brocade borders, and cinched with a matching patka over white churidars. He explained that nature/God gives us the elemental heartbeat wherein is derived the teen taal or sixteen beat measure, upon which all things are based. No matter how complex the variations we engage in, we return to the first beat, One, to complete a cycle. Because the heartbeat responds to emotional changes and physical movement with its own variations, he said, the emotive and descriptive components of a narrative can be closely depicted through fine rhythmic variation. This he demonstrated briefly with his ghunghat (bells), even portraying silence and calm with a low rustle denoting something like a Brownian movement, punctuated with low level events that barely scraped the narrative

Normally, I rail against lecture demonstrations, but here the lecture was pithy and the demonstration not to be missed. For his first appearance onstage, Pt. Maharaj wore a a fine golden necklace over his pale cream Akbari jama, tied on the right, embellished with Benarasi brocade borders, and cinched with a matching patka over white churidars. He explained that nature/God gives us the elemental heartbeat wherein is derived the teen taal or sixteen beat measure, upon which all things are based. No matter how complex the variations we engage in, we return to the first beat, One, to complete a cycle. Because the heartbeat responds to emotional changes and physical movement with its own variations, he said, the emotive and descriptive components of a narrative can be closely depicted through fine rhythmic variation. This he demonstrated briefly with his ghunghat (bells), even portraying silence and calm with a low rustle denoting something like a Brownian movement, punctuated with low level events that barely scraped the narrative threshold.

threshold.Then came robust improvisations on teen taal, followed by superbly enunciated narratives, original bohls he had composed, depicting episodes in the life of Krishna.

Saswati Sen, one of Guru Maharaj's primary disciples, and a famous teacher herself, opened her presentation using a time

Saswati Sen, one of Guru Maharaj's primary disciples, and a famous teacher herself, opened her presentation using a time cycle of nine and a half beats, then used various similar complexities to render Valmiki's highly emotional story concerning the seduction of Ahalya, wife of the Maharishi Gautam, by the demi-god Lord Indra in disguise, followed by her punishment by ossification and subsequent rescue by Lord Rama.

cycle of nine and a half beats, then used various similar complexities to render Valmiki's highly emotional story concerning the seduction of Ahalya, wife of the Maharishi Gautam, by the demi-god Lord Indra in disguise, followed by her punishment by ossification and subsequent rescue by Lord Rama.By then,

I was seeing

for the first time

exactly what

my own Kathak guru, Prahlad Das,

had meant by his mild but constant admonition, "Arms like snakes, hands like butter, and remember that each of your bells represents a star in the sky."

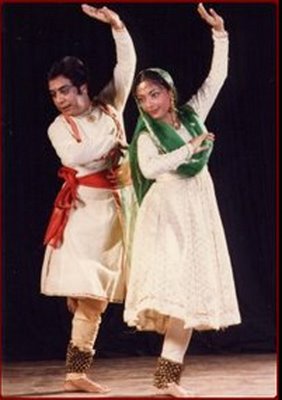

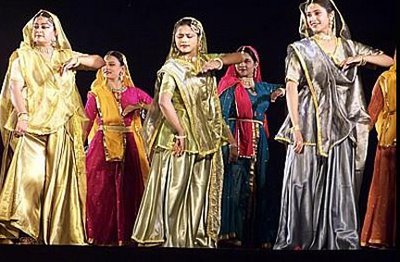

The second half was all performance, and presented Mahua Shankar (below, center), whose extraordinary duet with Saswati Sen showed how soon the mantle would be passed to her.

Maharaj highlighted the interplay of tabalchi and dancer before launching into tales from the Udhav Geeta, in which Krishna tells his friend Udhav stories of his youth. In the final piece, set in Raga Kirwani, Saswati Sen and Mahua Shankar again filled the entire stage, their brilliant long ghagras awhirl over bright churidars that matched their cholis, demonstrating amazing coordination and counterpoint, beautiful balance and sinuously suggested mudras. There was, nevertheless, an additional, idiomatic subtlety in Saswati Sen's every movement that I could barely catch, let alone describe. This level of subtlety was still to develop in Mahua Shankar's sparkling peformance, despite her virtuosity and fluid grace, but it will surely follow. Perhaps one just has to live that much longer to know time and timing as such an old friend.

Maharaj highlighted the interplay of tabalchi and dancer before launching into tales from the Udhav Geeta, in which Krishna tells his friend Udhav stories of his youth. In the final piece, set in Raga Kirwani, Saswati Sen and Mahua Shankar again filled the entire stage, their brilliant long ghagras awhirl over bright churidars that matched their cholis, demonstrating amazing coordination and counterpoint, beautiful balance and sinuously suggested mudras. There was, nevertheless, an additional, idiomatic subtlety in Saswati Sen's every movement that I could barely catch, let alone describe. This level of subtlety was still to develop in Mahua Shankar's sparkling peformance, despite her virtuosity and fluid grace, but it will surely follow. Perhaps one just has to live that much longer to know time and timing as such an old friend.Something had possessed me, at the end, to watch the finale of dazzling footwork by all three from the aisle, through binoculars, the better to make a swift exit and chase down to Chelsea. There, I found T.Coraghessan Boyle, poet-in-perpetuity of the Mid-Hudson Valley (Californian though he might be nowadays), wearing a choker of beads much shorter than Maharaj's over a bright T-shirt and an unsalted butter colored jacket. He was explaining to Andrea Lee and everybody else at Cedar Lake Dance Studios that his writing life followed a certain rhythm, which made him intersperse novel writing with short story telling. Andrea Lee, who wore black, with turquoise pendant earrings, demurred and said that only short stories offered the possbility of perfection-- something like a bohl, thumri or a gat, I suppose...

pictures from: asvari.org , pratappawar.com and Kalpana.it

<< Home