Sisyphus on 57th Street

John van Alstine, who lives within range of mountainous vistas, explained at the opening of his new exhibition that creating sculpture is a Sisyphean task. At least one guest wondered briefly whether this meant his sculptures topple down the mountainside on completion - but of Sisyphean Circle III, 2005 , 44 x 42 x 19 inches,course they don't.

at Nohra Haime Gallery through March 14 Why this should be is largely for John to know and everyone else to guess, especially as at least one element in each composition appears to be caught in flight. This collection in particular, scaled down but not domesticated by any means, explores the interaction of natural forces and industrial products by revealing the delicate subtleties of corrosion

on the polished surface of the steel and the internal structure and history of the pieces of slate, including a bloom of pale script lichen on one piece. Besides displaying the vitality of sustained effort, the other Sisyphean aspect of John's works - his material gamesmanship, or, if you will, his challenge to the gods - is as visible here as in his monumentally scaled works or in his larger installations in private settings - here are more pictures from his web site.

Above left, Dayton Pointe, 2002. On the right, Fleche III 2005, slate and steel.

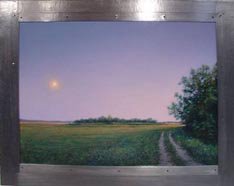

Also at Nohra Haime Gallery, Adam Straus' paintings, on the other hand, revel in low, flat and wide sea-level horizons, and present the interface of his luminous landscape paintings with their riveted, lead-faced encasings. Moonrise being the essential ingredient of these nano-narratives about the intrusion of artificial light, these are views of nature desiccated under challenge from

machines. Each painting in this sophisticated collection looks limpid from about five feet away, but on closer inspection, is heavy with multiple layers of pigment and glaze, dried slowly at low temperatures and lower light, to build up a heavy base for impasto flourishes.

machines. Each painting in this sophisticated collection looks limpid from about five feet away, but on closer inspection, is heavy with multiple layers of pigment and glaze, dried slowly at low temperatures and lower light, to build up a heavy base for impasto flourishes.Moonrise: Long Island Country Road, 2005, at Nohra Haime Gallery through March 14.

Leaving the Fuller Building, a group of guests pondered the restored finish of the Art Deco bronze reliefs on the elevator doors. Then, noticing the date inscribed in the floor mosaic in the lobby, which said 1902 to commemorate the Flatiron Building, also built by the George A Fuller Company, everyone became confused. Some wondered how much it had cost to maintain the marbled lobby of the Fuller Building for a century. Others said marble facing on interior walls had survived over the millenia in Rome and so would also survive, possibly for millenia, in New York.

Floor picture: courtesy Michael Leland

<< Home