Brand Vogue

A substantial and informative editorial in the April issue of American Vogue had this to say about the Internet: ‘…in a world flooded with information and images, and opinions about fashion and so forth, how does Vogue keep its authority? … (we) keep three things in mind: 1) Aim high --very high….2) Have fun....3) Keep your influence by exercising it.

A substantial and informative editorial in the April issue of American Vogue had this to say about the Internet: ‘…in a world flooded with information and images, and opinions about fashion and so forth, how does Vogue keep its authority? … (we) keep three things in mind: 1) Aim high --very high….2) Have fun....3) Keep your influence by exercising it.No doubt managing the production of an encyclopedic tome of advertising and content every month is a heroic -- indeed, Herculean -- task, but the editorial content is still the reason one looks at Vogue (we can see many of the ads in other magazines). Sadly, the editorial content of American Vogue is no longer providing the constant visual

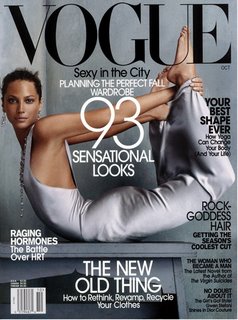

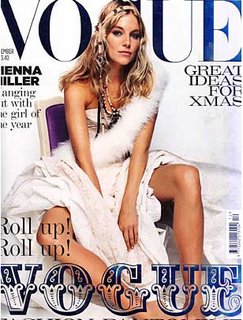

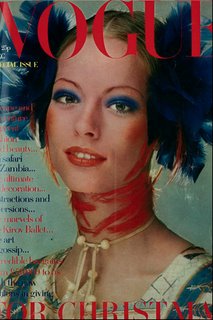

reordering and reexamination that gave its earlier versions their cachet. While American Vogue has turned to positioning itself as a socio-political arbiter and instructor for normative though expensive taste in the United States, in other countries, other editions are still carrying the torch for the art of dress. Sienna Miller exudes considerable mystery and glamor on the cover of British Vogue, and shows her extraordinary knees, but only looks cute on the cover of a recent American issue. On the June cover of American Vogue, such an extraordinary being as Uma Thurman is made to look nearly unremarkable--quite a feat --even as the copy trumpets that she is exceptional, a "Single Mom, Insanely Gorgeous."

reordering and reexamination that gave its earlier versions their cachet. While American Vogue has turned to positioning itself as a socio-political arbiter and instructor for normative though expensive taste in the United States, in other countries, other editions are still carrying the torch for the art of dress. Sienna Miller exudes considerable mystery and glamor on the cover of British Vogue, and shows her extraordinary knees, but only looks cute on the cover of a recent American issue. On the June cover of American Vogue, such an extraordinary being as Uma Thurman is made to look nearly unremarkable--quite a feat --even as the copy trumpets that she is exceptional, a "Single Mom, Insanely Gorgeous."Nature does create human beings who reeducate the eye,

so that either one or two startling features - whether it’s a strangely high bridge on a long nose, bones that eclipse the musculature, disquietingly wide set eyes, iconic legs, a swan neck or a short upper lip - reside in perfect harmony with the rest, or the entire cast of features takes on a simultaneous twist, unique to the individual, a distinction that manifests itself independently of race. All this has not gone away in the

so that either one or two startling features - whether it’s a strangely high bridge on a long nose, bones that eclipse the musculature, disquietingly wide set eyes, iconic legs, a swan neck or a short upper lip - reside in perfect harmony with the rest, or the entire cast of features takes on a simultaneous twist, unique to the individual, a distinction that manifests itself independently of race. All this has not gone away in the  present production of human beings; such people are on the ramps in numbers and in those uncharted multitudes of images online, even on Vogue and W's own spin-off website, style.com. But they are just not being properly celebrated in print by American Vogue any more. Where is a close examination of the extraordinary looks of Jade Parfitt, Oluchi Onweagba, Hye Park, Britni Stanwood or Freha Beha? In its several older international editions, Vogue has long fostered such occurrences of extraordinary physical variation and

present production of human beings; such people are on the ramps in numbers and in those uncharted multitudes of images online, even on Vogue and W's own spin-off website, style.com. But they are just not being properly celebrated in print by American Vogue any more. Where is a close examination of the extraordinary looks of Jade Parfitt, Oluchi Onweagba, Hye Park, Britni Stanwood or Freha Beha? In its several older international editions, Vogue has long fostered such occurrences of extraordinary physical variation and turned these people into a presence as icons of the public imagination. Its domain has never before been the milquetoast appeal of regular features and doll-like limbs and torsos. For celebrating the strangeness of true human beauty, and to evolve ways of learning to see it, it has always been the way of art to make that strangeness even more so, and it has long been Vogue’s role to make high art out of dress as an extension of the face and body.

turned these people into a presence as icons of the public imagination. Its domain has never before been the milquetoast appeal of regular features and doll-like limbs and torsos. For celebrating the strangeness of true human beauty, and to evolve ways of learning to see it, it has always been the way of art to make that strangeness even more so, and it has long been Vogue’s role to make high art out of dress as an extension of the face and body.

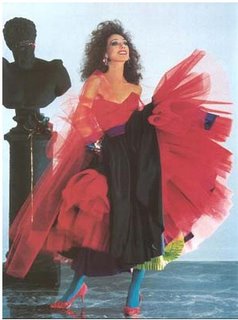

The outer limits of creative dressing and the art of constantly reinterpreting the body should still be what it’s about, not the practice of daily chic for successful professional women. Such chic would surely grow from within the individual who gained a continually re-educated eye. An image of a woman made very rich by marriage, heavily pregnant, well and beautifully exercised and boarding her husband’s jet in a gold bikini may be fun, but it is an image of consumerism, not art or design.

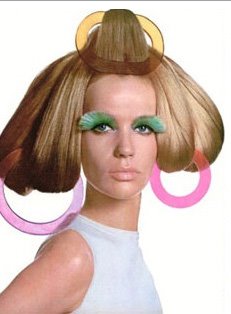

One thing that provokes my nostalgia for the inspired lunacy of the Vreeland years is the loss of American-sized scale still extant in her time.

Everything American was larger and bolder then, and expressed with a unique flamboyance and generosity of gesture that has now given way to a constricted kind of convention, as if career considerations still demanded dumbing down one’s dress sense -- which they don't, thanks in large part to the earier work of American Vogue itself. Which woman is it who can succeed professionally yet still needs nearly paint-by-numbers instructions on how to dress instead of having her eyes opened by radically new and demanding images? Out of those earlier times came, for instance, the uniquely American manner of mixing the simplest-looking and most disciplined couture with, say, tribal jewelry from distant parts of the world, combining Masai with Mainbocher, Cherokee regalia with Madame Grès. There is nothing comparable happening now. There are still distinctive British, French,

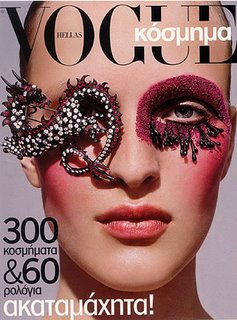

Everything American was larger and bolder then, and expressed with a unique flamboyance and generosity of gesture that has now given way to a constricted kind of convention, as if career considerations still demanded dumbing down one’s dress sense -- which they don't, thanks in large part to the earier work of American Vogue itself. Which woman is it who can succeed professionally yet still needs nearly paint-by-numbers instructions on how to dress instead of having her eyes opened by radically new and demanding images? Out of those earlier times came, for instance, the uniquely American manner of mixing the simplest-looking and most disciplined couture with, say, tribal jewelry from distant parts of the world, combining Masai with Mainbocher, Cherokee regalia with Madame Grès. There is nothing comparable happening now. There are still distinctive British, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Greek and Russian styles of luxury dressing, and to some extent a distinctive Australian manner, perhaps thanks to the smaller -- dare I say niche -- markets in which they are developed, and their distinctiveness is clearly expressed in their respective editions of Vogue. But American Vogue has lost its way in defining an ongoing, distinctive, high-end American idiom of dress for any or all parts of the country.

German, Spanish, Italian, and Greek and Russian styles of luxury dressing, and to some extent a distinctive Australian manner, perhaps thanks to the smaller -- dare I say niche -- markets in which they are developed, and their distinctiveness is clearly expressed in their respective editions of Vogue. But American Vogue has lost its way in defining an ongoing, distinctive, high-end American idiom of dress for any or all parts of the country.Teen Vogue now occupies the niche that Enid Haupt's Seventeen once created and then vacated in the process of chasing market share. It remains to be seen if Teen Vogue will serve as a feeder for grownup American Vogue, if that itself becomes nothing more than high-end pablum and a redundant pedestal for all things British, especially when British Vogue speaks so eloquently for superb creativity in Britain.

If the $3500 shoe is only extraordinary in materials and execution, but not in concept, it

remains pedestrian, and is a sign of what the market will bear rather than news of exceptional inventiveness, no matter where it is made. Where the formerly $300 shoe has become the $800 shoe, neither by reason of style nor as art, astonishing as that may be, its arrival is still only news of a new wave in consumerism and inflation, and its object will soon enough go the way of all knock-offs, even if the madly-priced first shot is made from the underbelly of baby crocodiles tanned with sperm whale blubber for three and a half years, cut by the one and only master of such things by the light of a new moon in August, formed on custom-made ebony lasts, then stitched by young nuns with small and lotion-free hands....

remains pedestrian, and is a sign of what the market will bear rather than news of exceptional inventiveness, no matter where it is made. Where the formerly $300 shoe has become the $800 shoe, neither by reason of style nor as art, astonishing as that may be, its arrival is still only news of a new wave in consumerism and inflation, and its object will soon enough go the way of all knock-offs, even if the madly-priced first shot is made from the underbelly of baby crocodiles tanned with sperm whale blubber for three and a half years, cut by the one and only master of such things by the light of a new moon in August, formed on custom-made ebony lasts, then stitched by young nuns with small and lotion-free hands....Superbrand Vogue is not new. The word vogue is not itself all that exalted; its etymology

has something to do with small boats, and the idea of being c

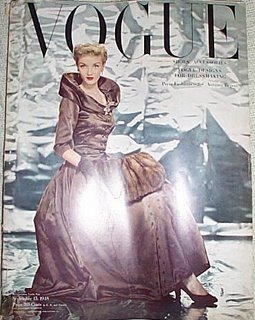

has something to do with small boats, and the idea of being c arried away on a wave of fashion. Yet there has long been a Vogue Brand, developed in connection with the magazine, which has consistently signified something loftier than what to buy next. It seemed nothing less, even in its early, numerically limited international editions, than a celebration of the most rarified appreciation of human beauty. Not the banal recognition of regular

arried away on a wave of fashion. Yet there has long been a Vogue Brand, developed in connection with the magazine, which has consistently signified something loftier than what to buy next. It seemed nothing less, even in its early, numerically limited international editions, than a celebration of the most rarified appreciation of human beauty. Not the banal recognition of regularfeatures and limbs and torso, but the startling reordering of thought when confronted with the new, such presentations empowered by the editorial luxury and panache of being authorized to introduce surprises.

Now, instead, we are obliged to admire conformity and manufactured luxe, just the way Jennifer Anniston is obliged to rework the ending of a movie to satisfy a test market’s disposition. If American Vogue is still to be counted as the flagship edition, yet displays such a dumbing down in pursuit of market share, then surely this represents a form of brand dilution for all editions of Vogue, worldwide.

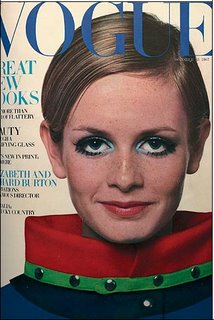

Now, instead, we are obliged to admire conformity and manufactured luxe, just the way Jennifer Anniston is obliged to rework the ending of a movie to satisfy a test market’s disposition. If American Vogue is still to be counted as the flagship edition, yet displays such a dumbing down in pursuit of market share, then surely this represents a form of brand dilution for all editions of Vogue, worldwide.The move from couture to expensive prêt-à-porter demands the worship of the normative

body—no more Twiggy as poster child for wraithlike atrophied-looking muscles (Kate Moss and others after her never were as skinny), nor any truly Amazonian turn of shoulder and rippling muscles like Veruschka’s. In terms of celebrating the human form, actors may be a fine addition to the visual menu, but for the purposes of celebrating human looks in particular, they are no substitute for the few people whose looks alone can carry them to fame.

body—no more Twiggy as poster child for wraithlike atrophied-looking muscles (Kate Moss and others after her never were as skinny), nor any truly Amazonian turn of shoulder and rippling muscles like Veruschka’s. In terms of celebrating the human form, actors may be a fine addition to the visual menu, but for the purposes of celebrating human looks in particular, they are no substitute for the few people whose looks alone can carry them to fame.While it’s a good thing that Condé Nast finally sent someone to have fun at Lakmé Fashion Week, if Vogue is going to have a Mumbai edition, there is one extra-aesthetic idiom, long set forth in older international editions, that should be set aside, even if market research indicates certain benefits for sales in America, and firmly put to bed: It has been the barbaric practice, at least since the ‘Sixties, as I recall, to set up location shoots for spreads where a waxed and polished blonde model is centered among men of other races who are seen as providing services to her, whether as camel drivers, fishermen, coolies or cabbies—in the last instance that I remember, Vikram Chatwal was sportingly announced as a kohl-wearing, emasculated cabdriver. This April’s issue turns from the “service” theme to a “separate but having fun” halfway house, as yet another blonde, this time Karolina Kurkova, is pictured here walking scantily clad among fully clothed men, including a driver who might carry her bags , and there sitting apart from deeply tanned Brazilians standing around, separated by her coloring and her seatedness, along with her polish, as if polish and liberty couldn’t exist apart from pallor – except that one of the fully dressed men is Pharrell Williams, who is allowed to massage a near-naked Karolina with lotion and escort her. The message of miscegenation is still clear, if modified. But now, that message, instead of being snotty, seems provincial and (no other word will do) finky—why relinquish the practice by degrees instead of doing away with it altogether?